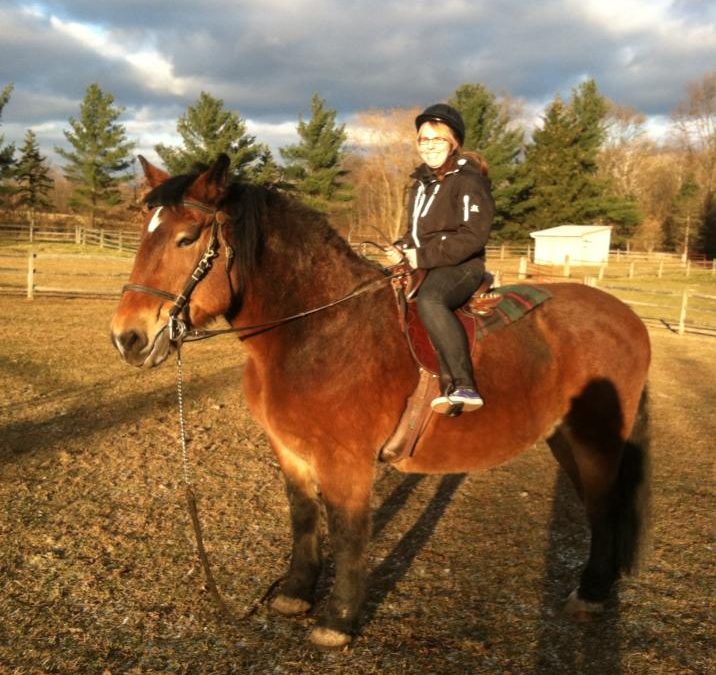

That dainty girl in the photo is my first distance horse, Tess (short for Serendipitous — she was). She went on to be a rock-solid trail riding partner for my friend, Dr. Barb. That’s not me, but a friend of Barb’s, whom Tess safely toted around, no doubt, because that’s the kind of girl she was. RIP, Tessy Noodlehead. Photo courtesy of Barb.

Live as if you were to die tomorrow. Learn as if you were to live forever. –Mahatma Ghandi

When we first got into the sport of distance riding, we were no Einsteins, that’s for sure. But we certainly had his enthusiasm for mistakes!

Let me tell you about our first competition.

It was a 20-mile Novice Competitive Trail Ride sponsored by OAATS, near Akron, Ohio, a mere 3 hour drive from home. Our sum total of formal education in the sport was watching Mollie Krumlaw-Smith teaching a brief segment at Equine Affaire in Ohio several months prior.

Richard was competing on his barely 5 year old Arabian, Shantih. I had my 4 year old draft cross mare, the one I’d purchased to do some lower level dressage with, Tess.

To say that Tess was a drafty girl would be like saying Shantih was “green broke.” Both are the kindest possible descriptions.

We’d “conditioned” a bit, riding at Allegany State Park on a loop of trail that we were quite certain must be about 14 miles in distance, which turned out to be about 8 or 9. (No GPS back then and we hadn’t a clue about pacing. We were out there for hours, it had to be a long way, right?)

Richard had purchased a “custom made” saddle for endurance. It was a thing of beauty. Did it ever really fit Shantih? I kind of doubt it, but by the time he was six and had gone from a spindly creature to a broad specimen, I guarantee you it did not.

We bought a used truck camper, entered the ride, left after work on Friday so that we could settle in and relax on Saturday and then compete on Sunday before driving home.

I neatly organized my clothes for the weekend and left them folded on our bed. They never made it to the camper.

We got a little confused on the directions to the ride camp, got lost (and almost broke up right there on the highway outside of Akron), and arrived at camp so late that no one was there to greet us. So we just parked out of the way, tied one horse to each side of the trailer with a hay net full of hay and a bucket of water, and called it a night.

Tess ate her hay in no time and reminded me –gently (as was her way)– to refill it, by kicking the trailer hub cap with her size four shoes, and if that was too subtle, she picked up her water bucket with her teeth and clanged that against the aluminum. The dents from both remain to this day, sort of a testimony to our ignorance and Tess’ love of an endless hay buffet.

Needless to say, we didn’t sleep much that night, and I had to make a shopping run the next day to buy some clothes to ride in. Fortunately, there was a clearance sale on these RED riding breeches at a local tack shop (I was not going to pay full price for something more figure-flattering), so along with some Walmart undies, socks and t-shirts, we were back on track.

We listened intently at the ride briefing. Ten miles to a hold, a vet check, then ten miles back to camp.

Dr. Maureen Fehrs, who saw my fear, no doubt, reassured me by saying, “Just think of it as a trail ride where a vet pops up here and there to check on your horse.”

Richard, always more competitive than me, was attempting to determine how fast he needed to go between various landmarks on the trail map, to make time.

The morning of the ride, I decided I’d better feed both horses “a little extra” (sweet feed, of course) to make sure they had the fuel they needed to get around the course.

When I mounted up before the start, I was suddenly confronted by 1500 pounds of drafty whirling dervish, a horse I’d never met before. What happened to my dear, sweet and quiet Tess?

Richard had his hands full too, but his answer to the mayhem was simply to Ride Fast. He left me on my behemoth mare and cantered ahead numerous times. Each time, I would catch up when they reached an insurmountable obstacle, like a bridge. Or a road crossing. Or railroad tracks. Each time, like Eeyore (“Oh bother”), Tess and I would give them a lead across and off they’d race.

He went on ahead into the vet check, wishing to not be “late” while I moseyed along, Dr. Fehrs’ words ringing in my ears, a lovely sight I am sure with my RED riding breeches and my dressage bridle and tack.

I learned a few things even in that ten short miles. If you have a wide and seemingly quiet horse, other riders will use her as brakes. I’m not sure how many times little Arabians bounced off Tess’ behind, or how many riders thanked me for being able to use her to slow their horse down. I was pretty sure that was not good etiquette, was grateful for my passive mount, and vowed I would try not to do that to someone else in the future. (Mostly, I’ve complied with my own dictate.)

When I got to the vet check, there was a bit of mayhem. Shantih had gotten away from Richard and spent the ten minutes of pulse-down time cantering around the area, and needless to say, had NOT gotten the best score for his heart rate.

Tess moseyed in, unfazed, pulsed down and vetted through, and ate as though she’d not seen a meal in a fortnight (more sweet feed, no doubt) and we headed back. Richard opted for safety at that point, and stuck with us.

At the final vetting, I leaned over Dr. Fehrs as she checked Tess over, worried that perhaps I’d done too much. “Are her suspensories sore?” Dr. Fehrs looked up after having palpated rigorously. “I’m not sure she even HAS suspensories!” (I’m pretty confident Tess’ cannons are about 10 inches in circumference.)

Long story short, Tess won the ride. I was hooked, Richard was mortified but also hooked, and on the drive home, when we stopped for fuel, I had to lift one leg (physically) at a time to get out of the vehicle. I have never been so riding-sore.

We were ill-prepared and overwhelmed.

We’ve never looked back.

We never stopped making mistakes.

We have never, I hope, stopped learning.

We never stopped looking around us, for people doing it well and not so well, to guide us along the way. We made friends and gathered dozens of informal mentors, generous people who subtly and not-so-subtly steered us on course. We listened when our friend Donna Shrader told Richard to stop screwing around with 25 mile CTRs and enter Shantih in a 50-mile endurance ride, fer cryin’ out loud. He did. They turtled. I listened when Mary Coleman told me Ned was a 100-mile horse. We got pulled from our first 100, but turtled our second.

Our horses busted out of pens. We learned that one of my horses was willing to limbo under a hot wire to join his friends if he had to, and bought a HiTie for him. We learned that riding crooked can create a sore back faster than just about anything and have cringed when our horses ducked away from our probing hands. We learned that pop-up tents and awnings do not fare well in wind storms. We learned that a farrier who won’t balance your horse’s feet properly, no matter how much you love him personally, could not be your farrier if you wanted your horse to stay sound. We learned that saddles that fit today may not fit six months from today, and that the side-pull hackamore that works just fine on your young horse for conditioning may not be nearly enough brakes for competition. I learned that perhaps asking your drafty draft cross to continue in the sport was too much to ask, but that you could find her a most amazing home with a CTR veterinarian. We learned that sweet feed was probably not our best feeding option, but that more in the way of supplements (offered willy-nilly to fix this or that) was not the answer either. I learned about concussions and helmets and about the fact that I’ve now, per doctor’s orders, had enough of the former for a lifetime. We learned about electrolytes through crampy hind ends and slow heart rate recoveries and, once, an erratic heart rate. I learned that I could be taught to pee on command whenever I saw a decent-sized rock or tree stump that could be used to mount a 16+H Ned. We learned that every single horse was a new and unique jigsaw puzzle by trying to do the same thing with one that we did with another, with abject failure as a result. We learned that time spent training was almost always wiser than time spent conditioning, and that rest was by far one of the greatest gifts we could give our horses. I learned that it was perfectly fine to change saddles and pads on a 100 if you happened to have bought the horse whose topline conformation would be captioned “Don’t Buy This Horse.” We learned how to read our horse’s eye, or a wrinkle of a nostril, or a change in impulsion. We found out that the difference between a 25- and a 50-mile and a 100-mile horse was often in the limited eye of the rider and their will to carry on and train for the longer distances. We learned that premature speed was nearly a sure-fire way to shorten a horse’s career. I’m learning now that the most important trait of an endurance horse for a few-times-concussed almost-50 endurance rider is A Great Brain. I’ve learned how much harder the ground is at nearly a half-century than it was at 32. We have learned to Make Haste Slowly. We have learned that there is nothing better than riding your twenty-something horses who are still sound and happy to go down the trail.

In almost every single case, we learned at the expense of our horses.

I don’t make that comment lightly. More than once, I’ve cried in a mane, apologizing. I’ve had big blubbering racking sobs over shortening the career of my 100-mile horse by not listening to my gut when I knew his feet were not right.

When we see someone making a mistake we’ve made, I cringe, I die a little inside. Not for them, not really, but for their horse. I swear that it rarely comes from a sense of superiority but from a place of empathy, a place of “Ohmigod, I’ve effed that up once and please don’t eff that up.”

(More than once I have asked my innermost endurance-tribe friends about a blog or article I’ve written, “Ohmigosh, did that post sound preachy? It sounded preachy, didn’t it? I mean, what do I know?, I don’t have ten bazillion miles. I’m no Hall of Famer.”)

But there is a funny thing about us horse people. I’m not sure exactly what it is. We are somehow convinced that we already have the answers. In some cases I’m ashamed to say, so did I, until my horses taught me that I was wrong. That’s the hardest way to learn. By hurting them. By miscommunicating with them. By asking them an unfair question.

As Walter Zettl would say in our dressage lessons. “Listen to ze horse. Ze horse, he always knows.”

At a ride last summer, a new rider arrived, a local horse trainer, at what I think was her first competition. She had six horses in a single wire of electric, not hot, dipping to about horse-knee level in some spots, and large enough for the herd –and it was a herd– to get up to a canter. She’d incorporated the ride management’s water tank in said paddock.

I walked over, grazing our boys, said a friendly hello, introduced myself, complimented her horses (sometimes this works) and suggested that perhaps all six horses in that same paddock might not be a good idea. We had some extra tape if she wanted to separate them, and did she have a fence charger? Told her about two horses that had run down the highway the year prior, both in the same paddock, how lucky we’d all been that they hadn’t been hit or injured. She told me they were turned out together at home. I explained for a bit that we’d found out the hard way that it could still spell trouble at an endurance ride camp. Could I help? She said “Well, I guess that works for you” and turned down my offer for help. It was said in a way that made me pretty sure any further input was un-welcome. I walked away as she explained to one of her students what an idiot I was.

Sigh.

Not my circus, not my monkeys, I told a friend. And then I thought about the horses, imagined them galloping down the busy road, or through MY horse’s carefully placed paddocks. Or someone else’s.

I found my friend, the Ride Manager, pointed out the situation, and she corrected it immediately, in a way that only the person in charge of the event could. She did the right thing.

How do we fix that person not willing to take good advice?

Damned if I know.

A tragedy occurred at a ride last weekend, one that many could smell was coming. Loose horses, then dead horses. Those are facts that cannot be disputed. So much anger, and outrage and calls for punishment and new rules and so much anger. Did I mention the anger?

About 80% of us are thinking about how we can change our own behavior to make things safer, not just for ourselves but for others. And for the horses. Always for the horses.

And the other 20%?

Okay, maybe it’s 90% and 10% … But those ten percent?

I’m not sure what we can do about them.

We built our Endurance Essentials course in a light-hearted but illustrative way. Focusing on the basics, the critical things that make endurance riders successful that may not be so obvious to riders from other disciplines, or riders new to horses altogether. It’s not rocket science. It’s also not kindergarten-like; our sport is too tough to gloss things over. I have a story for every single lesson we share; some more humorous than others.

You remember that line from Field of Dreams? (One of my favorite movies, and not just because Ray Liotta played Shoeless Joe Jackson.)

“If you build it, they will come.”

We will just have to wait and see.

Dare to make mistakes, but let them be frivolous ones, like the one I made wearing full seat riding tights for my first 100 (given Ned’s propensity for launching high into the atmosphere). It’s hard to explain the little bitty chafing scars all up and down your legs that you get where the stitching moves just a millimeter back and forth for 24 hours or so.

Happy trails all.

(Did that sound preachy?)