Year’s end is neither an end nor a beginning but a going on, with all the wisdom that experience can instill in us.

Everyone has a different way of coping. For me, it involves quiet time putting it all in perspective, organizing it in my head, and oftentimes, cathartically, writing about it. Sometimes I overshare. But there is something about putting it ‘out there’ that is healing. I cannot explain it. (I guess I am a writer.)

That leaves someone who actually has to do all of the heavy work, and that is my husband, Richard. We joke around that our division of labor means that I take care of everything that breathes; he takes care of everything that does not. But the reality is that we take care of each other, and this year has been a real challenge. The highest of highs, some pretty low lows, a lot of important things floating in a state of messy, some valuable (and thus, as a rule, difficult) lessons learned. Of course this means that I’ve picked it up and looked at it from all angles, in different light, like one might do with a pretty rock they find. (A normal person might set the rock down and walk on, or put it on a shelf and look at it from time to time. I write about the rock.)

Our collective resume, compared to that of so many legendary couples in AERC, could be printed on the cover of a matchbook, and we’ve never gone to the UAE, or won Tevis, or represented the United States at any endurance event where there was any chance of either of us standing on a podium. However, I sometimes think our values and goals align pretty closely with the majority of endurance riders; we focus on longevity in our barn, and have a goal for our horses if they seem suited to the game, to become 100-mile competitors.

So far, so good. We have two horses who are Decade Team partners and have successfully finished several tough 100s, and both are still sound and thriving.

Richard’s 18 year old Morgan/Arabian gelding, Sarge, is the AERC National 100 Mile Award recipient for the 2015 season, and his rides this year included the Old Dominion trail, arguably the toughest 100-mile course in endurance, twice. He won the Northeast Distance Challenge 100-mile ride in Maine, and got Best Condition, and capped off the season with a BC at the Carolina 100 over Thanksgiving weekend.

His 21 year old barnmate, Ned (Breezewood Nevarre) has carted me around for well over a decade now and is still the most dangerous horse in the barn, bless him. After a bit of a break as a second-stringer during which time he had major melanoma-removal surgery, he is back and finished the final ride of the season, a 50, in the front third of the pack, ably piloted by my friend Dawn.

Ace (Supreem Aviator), my other horse, has done two 100s, not including the Vermont three-day 100, and is eight years into his decade of competition, with some soundness hiccups at the moment.

And then there’s the new guy, Wynne (HV Golden Septer), who Rich hopes to get to a 100 in 2016. He’s done multi-day rides, he’s proven that he is a game competitor; he’s one of the sweetest horses I’ve ever known, and more sensitive than his big, brash go-down-the-trail bravado would indicate at face value.

So I spent some time thinking about the lessons we’ve learned (vast) in the sport of endurance riding, and the focus of today’s blog is this:

Apart from competing in our sport in general, what does it take to get to Decade Team? How do you build a 100-mile horse? How do you do both?

[Disclaimer: I detest sounding preachy. In a sport that is about “whatever works” this is what has worked for us. Plenty of people with plenty of success will likely disagree with elements of our philosophy. That is one of the things that is so challenging about our sport. And so fun.]

As unsparkly as it sounds, our general advice is this:

Focus on the Basics

Long term success in this sport is all about fundamental horsemanship. This is why riders who are already good horsepeople tend to take to our sport like ducks to water; it’s why those who despite resources (aka money) and time and excellent horses cannot seem to get out of their own way, blowing through horse after horse, flashes in the pan who disappear after a short period of time. It is also why those new to horses, and new to our sport have a significantly steep learning curve ahead. Oh, but what you will learn if you are open to always learning more!

(For more on this topic, check out this blog: http://enduranceintrospection.com/wp/endurance-and-conscious-competence-or-not/)

Frank truth there. Go back and read it again. If you’ve been through several suitable horses and can’t figure out why you are so ‘unlucky’ or if several people in our sport have offered you similar-sounding advice — chances are the answer lies in your horsemanship, not your luck. (Chances are that you’re probably not reading this; most of the riders who fall in this category already know everything. How lucky for them; how unfortunate for the long list of horses they’ve left in their wake. Forgive my sarcasm, but talented, disposable horses in our sport is the sort of topic that gets me on a soapbox.)

This is not to say that good horsemen do not have issues with their horses. Not at all. We’ve had all of the following: horses with lameness issues, a tie-up, shoeing problems, suspected ulcers, sore backs, horse/rider asymmetries, and Sarge was treated for a post-completion ileus at a ride several years ago, very shortly after he stood for Best Condition (and got High Vet Score, and trust me, we contemplated the irony of that.)

I was told this at a dressage clinic once, and I think it fits here: “Pros have bad moments too; the difference between them and the amateur is how they recover.”

If you are watching your horse like a hawk, you might get caught once, or you sniff a problem coming, and you address it.

Example from this season:

Sarge loves the Apple Wafer Treats we get from the feed store. They are his favorite goody, and Sarge is a cookie monster; he will beg for a treat every time you walk by his stall or paddock, and trust me, he gets a lot of treats. Between his third and fourth 100 this season, despite having had his teeth floated in the spring, Rich noticed that Sarge was turning his head to the side in a strange way as he ate the treats. Rather than ignore it, we had the vet check his teeth, and sure enough, a sharp edge on a molar was just beginning to create an ulcer. A little float and dental tune-up and he was back to normal status.

Now, would that issue have changed his season? His career? Maybe not, but it’s focusing on those small changes that prevents big problems down the road.

New riders often ask me about windpuffs, which are essentially tendon sheath filling, after a conditioning ride. Are they an issue? Well, as in most things endurance, the answer is “it depends.” Windpuffs that are old and cold and there morning, noon and night on a 14 year old horse that always appear the same way in the same situations and are unassociated with a lameness? <shoulder shrug> New windpuffs on a younger horse when the work has been made harder? That would concern us.

Similarly, Sarge had, unusually, little appetite at a hold halfway through the National Championship 100. Was it an ulcer? Was the pace too fast? Was it the ride management-supplied grain that he ate at the previous hold, pushing aside his own feed, in the epic phenomena we all know as Other Horse’s Feed (always yummier than their own). Unsure of which, we addressed them all. Rich slowed down and walked Sarge in to the next stop and go, where he began eating like he should. We treated him for ulcers after that ride, added Succeed to his rations for the rest of the season, and we won’t let him overindulge in an unfamiliar grain ever again.

We make mistakes. A lot of them. We just tend to learn from them.

Quickly. Most of the time.

The rider is a critical part of the partnership too. Like the horse, they don’t need to be perfect. We are proof of that.

Richard has significant health issues. (See my June blog, “An Old Wife’s Tale” for more details.) With Type 1 Diabetes (more typically known as “juvenile diabetes”) and chronic pain, he probably has more physical challenges than most 100-mile riders. But as I kept reminding him when he started to talk about trying a 100 mile ride, the move up from 50 to 100 is primarily mental, the ability to pace one’s adrenaline and to continue on, even as issues arise and get resolved, long past the point where the body and mind dream it is possible to go on.

Mental toughness Richard has. He learned techniques to manage and monitor his blood sugar levels, and keep his pain level to the point that he was able to continue to ride. Concerned about his own heat acclimation, he opted to split wood during the heat of the day throughout the competition season so that he was best prepared to ride during the legendary heat and humidity of the average Old Dominion or Vermont 100.

It Takes A Village

Thanks, Hillary Clinton.

Ride successfully completed. Horse chowing down and cozy in a blanket. This is clearly a post-ride in-depth analysis in New Jersey with Dr. Pam Karner, one of our tribe. Photo by Michelle Rice.

We make it a point to surround ourselves with the best resources we can find and exploit them to the fullest.

If we cannot become proficient about some specialty, we don’t. We bring in someone who is an expert and we trust them to help us get it right, with our feedback and guidance. We pay attention to changes and we communicate these to the members of our team.

We’ve had the same saddle fitter forever. Ann Forrest of Equestrian Imports is a former Grand Prix dressage trainer from Scotland. Years ago, when I was focused primarily on dressage and on the BoD of WNYDA, we brought her up from Florida to teach an educational saddle fitting clinic and make flocking/fitting appointments for our members.

I believe Ned was four and had no power steering when Ann first came to our area. He has a horrific topline, one I describe as captioned in horse conformation books simply — “Do Not Buy This Horse.” I am not a featherweight rider. Ann has helped us keep Ned’s back happy for all of these years. She is not interested in selling one particular brand of dressage saddle; she fits them all. One time she even, in oh-so-DQ fashion (we swore she held her nose as we did s0), helped me tweak the fit of my Bob Marshall Treeless Saddle. It took her about four nanoseconds to pinpoint the problem. Check.

Is Ann cheap? Nope.

But saddles with slightly narrowed/widened trees, flocked every year and someone we can email a photo to mid-season with the subject line “Help!”, and an expert assessment of which saddle/girth/pad for which horse and why, and horses who rarely, if ever, palpate backsore?

Priceless.

And we palpate. A lot. Hard. The day after every conditioning or competition ride, and just often in general. See above about resolving little problems before they become big problems.

Likewise, we have a local dressage instructor who keeps us on the straight and narrow. We’ve even gotten Dorothy to condition with us, and do some Limited Distance rides and she’s planning to join us for a fifty one day soon.

Is riding correctly and focusing on fixing our riding asymmetries sexy and fun? Not at all. (Richard calls lessons “torture.” Don’t tell Dorothy.) Is it important? Exquisitely.

A horse who no longer feels absolutely even on both leads, both diagonals? That smells like trouble.

See above about focusing on little issues early on …

We have a lameness guru veterinarian we count on, a friend who wrote the book on myofascial release for horses, friends with bits and pieces of electrolyte knowledge that we put together to make our electrolyting decisions, and another chum who is a nutritionist/veterinarian whose counsel caused us to make a few feed changes. Heck, Ned even has a psychic friend who lets us know his opinion on things. Trust me, Ned has opinions.

And the horses tell us, if we listen and watch carefully, which of those members of the village got it right. In the end, it is only the horses’ opinions that really matter in our sport.

We talk and tweak and discuss and cogitate on all of it. We bounce ideas and strategies and struggles with other trusted friends in our sport. We learn from each other; we cajole, we admonish, we advise. This is our tribe, and this input, this back and forth, it is invaluable.

Syl Madden, aka “Phyllis”, contemplates the pile of crew stuff that will theoretically fit in the back of the pick up for the VT 100. (Yes, most of it fits but some of it might bounce out at, say, Mile 85 or so.) Photo by Rachel Lodder.

Each horse is different. That is fundamental and a lesson best learned early on in this sport. Physiologically, psychologically.

I describe each horse as a jigsaw puzzle, and while solving them can be a bit humbling, it is also the most addictive part of the sport for me.

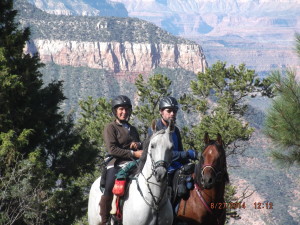

[And as an aside, riding in different parts of the country, totally different. Our electrolyte protocol when riding in the Northeast Region in the summer (hot/humid) was wildly different from when we rode in the XP Rides at Bryce Canyon and the Grand Canyon.]

Rich and Sarge several years ago during their first season of AERC competition — photo by Kate Rogers, Sweet Meadow Arts

For example, Sarge and Ned have been pretty simple from an electrolyting perspective; a steady dose every hour or so through the course of a ride, the same on 50s and 100s, higher doses when it is hot or humid, preferably in their wet slushie at the hold, syringed on trail on longer loops, preferably right after a big drink. Better a half dose more frequently, than a big dose less so.

Ned getting a dose of Perform N Win electrolytes in his slushie at the 65 mile hold of the Canadian National Championship 100. Photo by Rachel Lodder.

Ace and Wynne required more tweaking, it took a conservative Rider Option pull for each horse early on during hot and humid 50s for us to figure them out. Ace needs more electrolytes at a higher dose before and during the first loops of a ride. Likewise Wynne. Both are hot horses who sweat away a lot of anxiety during the ride start and it takes its toll in electrolyte loss. Wynne taught us that with a lackluster appetite at the first hold, and a barely discernable heart arrhythmia mid-ride. (We messed it up again at a hot late spring CTR this year, resulting in a hanging heart rate at the finish, but I think we’ve now gotten the memo in bold face font. Electrolyte harder, earlier.) For Ace, it was a couple of hind leg cramps high up with no other factors to explain them.

At a pitcrew stop on the Vermont 100, Richard hydrates, Fred (Rich’s brother in law) sponges, and Patti is poised with a dose of Lyte Nows to be administered right before they hit the trail again. Photo by Deanna Ramsey.

Were those electrolyte pulls difficult? Not at all. Part of the imperfect learning process. They were the best decision for a horse on a day where more miles weren’t likely to be therapeutic. And we learned gobs to help the horse over the long term. Ka-ching, ka-ching. Keep your eyes on the prize!

While it takes a village, lifetime membership on our team is not a guarantee.

Our journey to find the right farrier has been excruciating but has a happy ending. Our gut feelings about our horses’ hoof care and protection got confirmed with more education on hoof balance and structure and function (thanks Daisy!) and x-rays on our own horses confirmed what we thought we knew. We may have shortened the career of Ace with our ignorance and lack of assertiveness and that weighs heavily on me, and over the course of our endurance career this is the subject matter I wish I’d gotten better educated on earlier.

Regrets? We have a few.

Why? Primarily because they came at our horse’s expense.

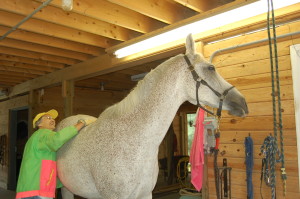

We’ve come a long way, baby. Ace gets his shoes pulled by Rusty Toth, 2012. Right front trimmed; left front shoe pulled only. This was four weeks from being shod.

Same horse, Ace, 2014, vastly improved. No foot, no horse. Learned this one the hard way at a horse’s expense.

Of all of our rider option pulls, I think I’ve had more related to shoeing and hoof balance than any other. Big pulls. On 100s.

We liked our farrier. I still miss him, personally, to this day. But the most likeable and reliable farrier on earth can’t be a part of our team if we can’t get the hoof balance right, can’t address biomechanical and other issues as they arise, and can’t shoe to the varying conditions at rides without routine failure. We took a couple of brief detours, tried on a couple of farriers on for size, and they us. With the right farrier now, and enough education to trim and see issues as they come up, and in Richard’s case, learning the skill of nailing on EasyCare Performance N/G shoes, we are confident in this aspect of our horses’ care.

Lots of wear on Sarge’s left front EasyShoe after 100 miles of Vermont trail, but as we text jubilantly to Dave Augustine after every ride — “Shoe loss, zero point zero!”

And you should see my Mad Rasping Skills.

Rest, Rest, Rest

Maintaining the fitness and well-being of seasoned horses requires far less mindless pounding down the trail than some riders realize.

Because our winters in Western New York (think Buffalo, think lake effect snow, think about the fact that we live about ten miles from a ski resort) are typically so harsh [she types as the grass is green and as we wrap up the warmest December ever on record] that our horses all get a 6-8 week vacation every year whether we like it or not. I think this has been one of the secrets to our success. Everyone gets a break, any little subclinical strains or sore areas get a chance to heal, tummies assaulted by work and travel get a chance to digest the simplest of forages, shod feet get to be bare and expand and feel the ground without the burden of shoes.

They are barefoot, they are hairy, they get a little fat, they play “Bitey Face” when they get bored, we hop on from to time to trudge around on our snowy trails. We try to start booting and doing some work on the shoulder of our country roads come February or so. We took all four to Tennessee mid-spring to camp and condition, which gave us a jump start. We leg up in time for the first ride of the season as Mother Nature allows. This year it was Biltmore, in early May, and Sarge had not done a single conditioning ride more than 18 miles. Richard signed up for the 75. Sarge handily finished, not racing, but he proved once again that judicious, planned, progressive conditioning and plenty of rest are key to a mature horse’s success. We see this season after season. We worry about the horses’ level of fitness at the first competition of the season; every year the horses tell us they are plenty ready. (We, on the other hand, walk funny for a few days.)

In fact, Richard says one of the bummers about the 2015 season was how little he actually got to ride Sarge. After each 100, his shoes got pulled, he got turned out to rest and relax and heal and recharge, typically for about four weeks, before Rich got on him again. The “tune up” rides between 100s were short and hilly and focused often on heat acclimation (the one aspect of conditioning that horses lose within days of ceasing work), as well as checking for any changes in biomechanics, or attitude. We are blessed to live in the foothills of the Allegany mountains, so for us, hillwork is a given, but for the last ride of the season, the relatively flat Carolina 100, Rich sought out flatter roadwork to prep. Since conditioning in sand is not an option for us, Richard simply walked all of the deep sand at the ride.

Never underestimate the importance of rest.

Ace and Ned catch a few zzzzs the morning after completing the Canadian National Champion 100. Photo by Rachel Lodder.

Keeping It Fun

Sarge has a work ethic like no other horse we’ve ever owned. Solo, in company, regardless of heat or trail conditions (flat, poundy, mountainous, rocky), heading to or away from home (or base camp at a ride), Sarge attacks the trail. About the only thing he hates is mud, and even that doesn’t slow him down; it just pisses him off and he might scrape off your leg on a tree to avoid it.

But let’s face it, that’s unusual. Ned has never had that sort of freakish enthused work ethic. Getting and keeping him fit this season meant a little trickery, a little horse herd psychology manipulation, and a lot of compromise. Especially after three seasons of pretty-close-to-retired. At 21, he hardly looks at our home trails and rubs his hooves in enthusiastic glee. However, he feels a less than benevolent sense of competition with Wynne, so a conditioning ride with Wynne brought out a lot of not-always-pleasant hijinks, but a whole lot more brilliant effort, work-wise. On the days Ned found conditioning to be a chore, we just went out and explored some new trails and trudged up and down and around our little mountain. I resisted the temptation to nag him, as that spoils his attitude in the blink of an eye. Or as an alternative, we headed to the arena to do some dressage schooling, as Ned does love to dance. Since he has a fairly decent education in this area, it’s also some significantly challenging weight-lifting type of work. A half hour of (rusty) second level schooling goes a long way to getting or keeping the old man fit.

He got even fitter than I realized. Given the opportunity to keep up with his arch enemy, Wynne, on a flat, sandy 50 in November, he pulled on my friend Dawn so hard that he bloodied and blistered her fingers. Not what I expected, and as a member of the tribe said, a lousy way for him to prove to us that he should be retired.

My guy, Ace, is just a little different. He’s an earnest and anxiety-ridden guy, and while he physically does not need to work more than a couple of times a week to stay fit, I find that doing some kind of mental work with him (a little dressage, some ground work/free longeing) keeps his brain engaged and his body loose. Given the same sort of near-daily work, Ned would go on strike.

Jigsaw puzzles, every last one.

In summary, with seasoned horses (5+ more of steady work/conditioning/training) we use judicious and varied work to bring the horses up to fitness when they’ve had a break. We both travel for work; before a planned trip, we condition fairly hard knowing the horses will be resting while we are away. But when there’s a go/no go call to be made, we almost always err on the side of rest, unless it is to work on heat acclimation. It has not failed us yet, for the physiology or the mental well-being of the horses. For 100s and veterans, it is always better to arrive at a competition well-rested and free from any metabolic or biomechanical “owies” than it is to arrive over-conditioned, a little tired and a bit sore somewhere. We believe this whole concept can mean the difference between a lengthy and an abbreviated career in our sport.

Best Laid Plans

In this sport, we’ve learned it’s prudent not to get terribly attached to your plans for any single ride or season.

Our favorite ride is the Moonlight In Vermont 100. It was the first hundred both of us completed and all three of our 100-mile horses have finished this tough mid-July ride quite handily. Rich had planned this ride for Sarge five weeks after he’d top tenned the Old Dominion.

But a little virus that some rider brought to an Ohio ride in late June changed those plans. Ten days after the Ohio ride, one of the horses we took developed a fever and a cough. We isolated our horses, we took temperatures any time one of the horses looked NQR (not quite right), we watched as it worked its way through almost everyone in the herd. Sarge seemed to dodge the viral bullet.

Richard entered Vermont, he packed the trailer, we set the alarm at 3 am to leave for Vermont. As I headed to the barn in the dark, I heard a horse cough. I collected Sarge, put him on the cross ties, took his temperature. He coughed once, carefully, as I removed the thermometer. I didn’t even need to read it; we weren’t going. But for the record, his temperature was 101.3.

Timing is everything.

[And as a little Public Service Announcement, if you don’t already, get a thermometer, know how to use it, and please don’t bring your sick or contagious horse to a <bleeping> endurance ride. For the record, a fever often precedes symptoms, which means your horse might be feverish, contagious and ill even before he show symptoms. A thermometer. About five bucks at CVS. Hugely critical concept doing what it is that we do. Please. Sorry, preachy.]

Likewise, Ace took a few NQR steps this spring. Just a few. Only in certain footing. So subtle I couldn’t be sure of which front leg. Diagnosis: ringbone, with a side of compensatory subtle soreness in other limbs. Likely the result of his calf-kneed conformation and accelerated by the ‘forward foot syndrome’ I’d begged our previous farrier to address, repeatedly, and without success, for years. I’d planned to do a 100 or two with him this season; instead we opted for a number of treatment protocols and some corrective shoeing, and ended up pulling his shoes and giving him a vacation. We’ll see how he looks in the spring. After eight plus seasons of competing well, he doesn’t owe me a thing. If it is a retirement from competition that he needs, that is what he will get.

Wynne and Ned were my Plans B and C.

Wynne, a big bay gelding who is relatively new to our herd, and who I’d only ridden once or twice gave me a humbling downhill ride at an uncomfortably fast clip. He cantered off, head between his knees as a reaction to an unsubtle correction on my part, and I quickly learned his hackamore was not adequate in the brake department. A concussion, a big bruise, a damaged ego. Back to the drawing board with a new Myler combination bit, some dressage schools to ensure that he and I were both confident that I could stop him any time I wanted, but I had a new-found respect for this powerful and sensitive horse.

Time for a new helmet. Parted ways with Wynne and was handed a humbling lesson about getting a little cocky when correcting a big, powerful and sensitive horse.

We did half of a 50 up in Canada, where I pulled him just as we started to deplete the fun meter. Wynne and I calmly negotiated the pace on the first loop; I controlled the urge to use my voice or behave in a way that he could interpret as punitive. It was a fair compromise; neither of us entirely happy but still liking one another. We put a lot of pennies in the jar of our growing relationship. I could tell I needed to tweak his treeless saddle fit, he was starting to use one hind more than the other, and with all As, we called it a day, and crewed Sarge and Rich to a top ten completion.

I rarely regret a rider option pull. This was no exception.

A few weeks later, Wynne won and got Best Condition at the Northeast Challenge 50 in Maine. An epic weekend because Richard and Sarge won and got BC in the 100 as well. We contemplated, jokingly, quitting the sport after that weekend. How could we possibly top that one?

On our way to first and BC at the Northeast Challenge. What a pleasant surprise on what I’d entered with the intention to find a common ground about pacing. We found it. Photo by Clowater Arts and Photography.

But the best part about the ride, for me, was the fact that I’d seen it only as a training ride for Wynne. He got rushy and tried to take over the pacing when we came up behind other horses. Rather than fighting with him, I turned him calmly back up the trail away from them for a solid quarter of a mile, put on my gloves, got off, electrolyted him, and then remounted and insisted on a sane pace as we approached them, then passed them. You could almost see the light bulb come on over Wynne’s ears. He felt strong and calm, and even in both hind legs, and his saddle stayed exactly where it need to; we put a lot of pieces in the puzzle that day. And as we crossed the finish line, I had no idea we’d won.

The season didn’t really go as planned. We dug deep into our alternate plans a number of times.

Best to write competitions in to the calendar in pencil. There is always another ride.

Mind the MPH

As much as I love riding with my husband, it’s not always in my horse’s best interest.

Asking my husband to slow down is not always in the best interest of my marriage. (Truth be told, I wouldn’t want to slow down my pace either.)

Moonlight in Vermont 50 with Sarge and Ace. We rode together, we top tenned, we decided to stay married. But I guarantee I said “Can we slow down a bit?” at least 14 times during the ride. Photo by Mary Watkins.

Detaching Ace, who has separation anxiety, from any of his barnmates, unpleasant at best.

This has meant some strategic decision-making which means that someone is always compromising. In the end, the slowest horse sets the pace for the day, if you are thinking long-term goals.

Sarge has rather effortlessly competed his decade of competition at a rate of speed that exceeds Ned’s by a bit and well exceeds Ace’s.

Ned, physically, seems quite capable of keeping up with Sarge or Wynne on most days, but he doesn’t always want to. Is it worth it to tread on his attitude to push him along? Not for me, not with Ned.

Ace, physically, is not capable of keeping up with Sarge or Wynne, but he would try. How can I tell? Because when he tries to keep up, he’s not in his “sweet spot.” He feels just a little rushed, just a little klutzy, a little anxious.

It is not always easy to juggle the needs of the horses and compromise. But we do the best we can.

But that is the subject of another blog, for another day, about how to stay in a long term marriage competing in this sport …

Getting tacked up in Vermont. We are still in love because I haven’t asked him to slow Sarge down yet. Photo by Dale Gurney.

Until then, happy trails!